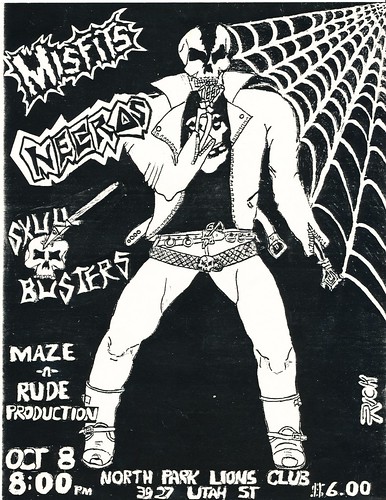

Tesco, duly impressed, became our pal. One night he invited us to a party that his little band, the Meatmen, were playing at a storage space in the suburbs. In attendance was a cadre of ridiculous teenagers that Tesco knew through the magazine. They called themselves the Necros and were led by a portly, pimply red head named Barry, who looked like an adolescent version of Curley from the Three Stooges. Barry was bent on being the most ridiculous parody of what punk rock was supposed to be, screaming, pouting, and drinking beer from a keg via the nozzle. Remember the punk episode on "Eight is Enough?" Barry was out of central casting for that, a little fool.

Tesco, duly impressed, became our pal. One night he invited us to a party that his little band, the Meatmen, were playing at a storage space in the suburbs. In attendance was a cadre of ridiculous teenagers that Tesco knew through the magazine. They called themselves the Necros and were led by a portly, pimply red head named Barry, who looked like an adolescent version of Curley from the Three Stooges. Barry was bent on being the most ridiculous parody of what punk rock was supposed to be, screaming, pouting, and drinking beer from a keg via the nozzle. Remember the punk episode on "Eight is Enough?" Barry was out of central casting for that, a little fool.The summer of 1980 was a storm of Fix appearances in Michigan. Empty joints in Detroit, Flint, Lansing, Kalamazoo, all of them found the Fix blaring away to no one. We played a biker fest in a field in northern Michigan and were embraced by the methed-out crowd, who had to respect the sheer velocity of the music. One Friday night we sat on our porch after a rehearsal in the basement of the Lansing house Mike and I shared, drinking, kickin' the Pork Dukes, and one of our neighbors came by. The 'hood was a mix of black ghetto and white trash, and our ebony and ivory band fit nicely, aesthetically, anyway. This neighbor was of the white trash influence, but he liked us and cadged weed from us on occasion. So he had a deal and we listened: His dad ran a bar in St. Johns, a farming town about 30 miles north of Lansing and the weekend house band had backed out at the last minute earlier that day.

He could get us $300 a night plus beer for three sets a night for the weekend. By this time, it was 7 p.m. and we were well into our buzz, hitting off 40-ouncers and the occasional pull on a bottle of bad whiskey.

Of course we'll play.

We loaded up the gear and drove out there, conveniently missing a sound check but in time for a 10 p.m. first set. We launched into our version of "Tell Me," the Stones song so adroitly covered by the Dead Boys. We moved through some other covers we had, like "Build Me Up Buttercup." Blank stares. How about a version of the Monkees' "I'm a Believer?"

"Slow down," one of the sodden regulars yelled at us.

Bar boss was getting a bit miffed. Fix guys getting a little used to being stared at. But we were also used to moving through the set quick, which we did, giving them maybe 30 minutes of noise like they had never heard before and would never hear again. The bar paid us $300 and asked us not to play any more.

"And if you don't mind," the boss said, "could you leave? You're making these people uncomfortable."

We played a roller skating joint in Flint one weekday afternoon, and when we were done, sat in the locker room drinking wine while the kids and their parents filtered through. At times the Fix looked like boys caught between trashy glam and MC5/Stooges bare bones glitter. Hair was longish, booze was ubiquitous and the girls who traveled along as seedy as us. Those girls; we were being taken for a ride by some of them and we dug in.

At the same time, we honed our craft, though, and the songs came fast and furious. We would find covers to work in, old three-chord pop songs by bands like Paul Revere and the Raiders and the Box Tops that lent themselves willingly to our sound, which kept getting faster and faster.

In Detroit, we played at a place called Nunzio's, a shitty little enterprise in Lincoln Park that nobody went to on weeknights, which is when we came to play and get our $25. Within two years, the place would be taken over by copycat punk bands who dragged 20 of their best friends along to be part of their little club, making Nunzio's a happening place for about 10 minutes.

We also played the Red Carpet, getting some Sunday night shows to practice on a stage. These were great shows for checking in new material, and we would sometimes play the set twice to fulfill an ageing rock promoter's idea of how bar music works: Two sets, at least. We just dove into our bag of covers to fill out a set that by the end of the year included "Vengeance," "Famous," "In This Town," "Candy Store" and some stuff that would never be recorded, like "You" and "Statement" (which is actually Alice Cooper's "Caught in a Dream" reworked). The Fix was blasting at these places to no one who understood or wanted to understand, and we did it because we felt it. There were none of our friends to impress and we didn't care. In September, Craig, Mike and I moved into a house at 823 Beulah across from the city zoo in Lansing. It was a three-bedroom dump in a shitty neighborhood that rented for $350 a month. The basement, which fit four guys, their gear and little else, was where we would write and rehearse all of the Jan's Rooms session as well as things that would never be recorded.

The practices were as frantically fast as our set -- 20 minutes and we-gotta-go. Figuring out a new song might attach another 20 minutes to a practice or two. "Off to War" and "Rat Patrol" took exactly that. By the time those songs came along in early '81, we were a machine that absorbed each other's thoughts. We wrote our parts telepathically, in fact.

We didn't know shit about what hardcore was or what any of those weak labels meant. We just played. We never tossed our Aerosmith or Zep records, either. We just took the new stuff that we would hear, like Black Flag or the Germs, and pushed it into the creative mix. I remember playing a show at Club Doo Bee, our local venue, and coming home and slapping on the first Psychedelic Furs lp. And it sounded good. We played what we did because we felt it, not because we were aping our heroes.